Index of a subgroup

In mathematics, specifically group theory, the index of a subgroup H in a group G is the "relative size" of H in G: equivalently, the number of "copies" (cosets) of H that fill up G. For example, if H has index 2 in G, then intuitively "half" of the elements of G lie in H. The index of H in G is usually denoted |G : H| or [G : H].

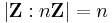

Formally, the index of H in G is defined as the number of cosets of H in G. (The number of left cosets of H in G is always equal to the number of right cosets.) For example, let Z be the group of integers under addition, and let 2Z be the subgroup of Z consisting of the even integers. Then 2Z has two cosets in Z (namely the even integers and the odd integers), so the index of 2Z in Z is two. In general,

for any positive integer n.

If N is a normal subgroup of G, then the index of N in G is also equal to the order of the quotient group G / N, since this is defined in terms of a group structure on the set of cosets of N in G.

If G is infinite, the index of a subgroup H will in general be a cardinal number. It may however be finite, that is, a positive integer, as the example above shows.

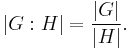

If G and H are finite groups, then the index of H in G is equal to the quotient of the orders of the two groups:

This is Lagrange's theorem, and in this case the quotient is necessarily a positive integer.

Contents |

Properties

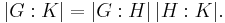

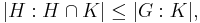

- If H is a subgroup of G and K is a subgroup of H, then

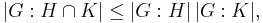

- If H and K are subgroups of G, then

-

- with equality if HK = G. (If |G : H ∩ K| is finite, then equality holds if and only if HK = G.)

- Equivalently, if H and K are subgroups of G, then

-

- with equality if HK = G. (If |H : H ∩ K| is finite, then equality holds if and only if HK = G.)

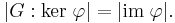

- If G and H are groups and φ: G → H is a homomorphism, then the index of the kernel of φ in G is equal to the order of the image:

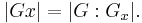

- Let G be a group acting on a set X, and let x ∈ X. Then the cardinality of the orbit of x under G is equal to the index of the stabilizer of x:

-

- This is known as the orbit-stabilizer theorem.

- As a special case of the orbit-stabilizer theorem, the number of conjugates gxg−1 of an element x ∈ G is equal to the index of the centralizer of x in G.

- Similarly, the number of conjugates gHg−1 of a subgroup H in G is equal to the index of the normalizer of H in G.

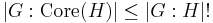

- If H is a subgroup of G, the index of the normal core of H satisfies the following inequality:

-

- where ! denotes the factorial function; this is discussed further below.

- As a corollary, if the index of H in G is 2, or for a finite group the lowest prime p that divides the order of G, then H is normal, as the index of its core must also be p, and thus H equals its core, i.e., is normal.

- Note that a subgroup of lowest prime index may not exist, such as in any simple group of non-prime order, or more generally any perfect group.

Examples

- The alternating group

has index 2 in the symmetric group

has index 2 in the symmetric group  and thus is normal.

and thus is normal. - The special orthogonal group SO(n) has index 2 in the orthogonal group O(n), and thus is normal.

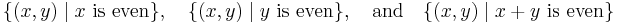

- The free abelian group Z ⊕ Z has three subgroups of index 2, namely

-

.

.

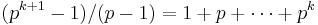

- More generally, if p is prime then Zn has (pn − 1) / (p − 1) subgroups of index p, corresponding to the pn − 1 nontrivial homomorphisms Zn → Z/pZ.

- Similarly, the free group Fn has pn − 1 subgroups of index p.

- The infinite dihedral group has a cyclic subgroup of index 2, which is necessarily normal.

Infinite index

If H has an infinite number of cosets in G, then the index of H in G is said to be infinite. In this case, the index |G : H| is actually a cardinal number. For example, the index of H in G may be countable or uncountable, depending on whether H has a countable number of cosets in G. Note that the index of H is at most the order of G, which is realized for the trivial subgroup, or in fact any subgroup H of infinite cardinality less than that of G.

Finite index

An infinite group G may have subgroups H of finite index (for example, the even integers inside the group of integers). Such a subgroup always contains a normal subgroup N (of G), also of finite index. In fact, if H has index n, then the index of N can be taken as some factor of n!.

A special case, n = 2, gives the general result that a subgroup of index 2 is a normal subgroup, because the normal group (N above) must have index 2 and therefore be identical to the original subgroup. More generally, a subgroup of index p where p is the smallest prime factor of the order of G (if G is finite) is necessarily normal, as the index of N divides p! and thus must equal p, having no other prime factors.

This result is generally proven using group actions; an alternative proof of the result that subgroup of index lowest prime p is normal, and other properties of subgroups of prime index are given in (Lam 2004).

Proof

This can be seen more concretely, by considering the permutation action of G on left cosets of H when multiplying them on the right by elements of G (or, equally, multiplying right cosets on the left). This provides a quotient group of G, the image of this permutation representation, which is a subgroup of the symmetric group on n elements.

Let us explain this now in more detail. The elements of G that leave all cosets the same form a group.

(If Hca ⊂ Hc ∀ c ∈ G and likewise Hcb ⊂ Hc ∀ c ∈ G, then Hcab ⊂ Hc ∀ c ∈ G. If h1ca = h2c for all c ∈ G (with h1, h2 ∈ H) then h2ca−1 = h1c, so Hca−1 ⊂ Hc.)

Let us call this group A. Let B be the set of elements of G which perform a given permutation on the cosets of H. Then the cardinality (size) of B is equal to the cardinality of A, and in fact B is a right coset of A.

(If cb1 = d and cb2 = hd (a member of the same coset as d), then cb1b2−1 = db2−1 = h−1c ∈ Hc. Since this is the case for any b2 and for any c (with appropriate d), b1b2−1 ∈ A and the size of B is less than or equal to the size of A. Conversely, Hcb1 = Hcab1, and since the left-hand side is in Hd then so is the right-hand side: Hcab1 ⊂ Hcd, showing that for any element of A there is a different element of B, and thus the size of A is less than or equal to the size of B.)

Since the number of possible permutations of cosets is finite, namely n! (assuming H is of finite index n), then there can only be a finite number of sets like B. If G is infinite, then all such sets are therefore infinite. The set of these sets forms a group isomorphic to a subset of the group of permutations, so the number of these sets must divide n!. Finally, if for some c ∈ G and a ∈ A we have ca = xc, then for any d ∈ G dca = hdc for some h ∈ H, but also dca = dxc, so hd = dx. Since this is true for any d, x must be a member of A, so ca = xc implies that A is a normal subgroup.

Examples

The above considerations are true for finite groups as well. For instance, the group O of chiral octahedral symmetry has 24 elements. It has a dihedral D4 subgroup (in fact it has three such) of order 8, and thus of index 3 in O, which we shall call H. This dihedral group has a 4-member D2 subgroup, which we may call A. Multiplying on the right any element of a right coset of H by an element of A gives a member of the same coset of H (Hca = Hc). A is normal in O. There are six cosets of A, corresponding to the six elements of the symmetric group S3. All elements from any particular coset of A perform the same permutation of the cosets of H.

On the other hand, the group Th of pyritohedral symmetry also has 24 members and a subgroup of index 3 (this time it is a D2h prismatic symmetry group, see point groups in three dimensions), but in this case the whole subgroup is a normal subgroup. All members of a particular coset carry out the same permutation of these cosets, but in this case they represent only the 3-element alternating group in the 6-member S3 symmetric group.

Normal subgroups of prime power index

Normal subgroups of prime power index are kernels of surjective maps to p-groups and have interesting structure, as described at Focal subgroup theorem: Subgroups and elaborated at focal subgroup theorem.

There are three important normal subgroups of prime power index, each being the smallest normal subgroup in a certain class:

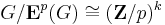

- Ep(G) is the intersection of all index p normal subgroups; G/Ep(G) is an elementary abelian group, and is the largest elementary abelian p-group onto which G surjects.

- Ap(G) is the intersection of all normal subgroups K such that G/K is an abelian p-group (i.e., K is an index

normal subgroup that contains the derived group

normal subgroup that contains the derived group ![[G,G]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3977a81444c9d8799fad00e62a3b3f78.png) ): G/Ap(G) is the largest abelian p-group (not necessarily elementary) onto which G surjects.

): G/Ap(G) is the largest abelian p-group (not necessarily elementary) onto which G surjects. - Op(G) is the intersection of all normal subgroups K of G such that G/K is a (possibly non-abelian) p-group (i.e., K is an index

normal subgroup): G/Op(G) is the largest p-group (not necessarily abelian) onto which G surjects. Op(G) is also known as the p-residual subgroup.

normal subgroup): G/Op(G) is the largest p-group (not necessarily abelian) onto which G surjects. Op(G) is also known as the p-residual subgroup.

As these are weaker conditions on the groups K, one obtains the containments

These groups have important connections to the Sylow subgroups and the transfer homomorphism, as discussed there.

Geometric structure

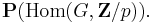

An elementary observation is that one cannot have exactly 2 subgroups of index 2, as the complement of their symmetric difference yields a third. This is a simple corollary of the above discussion (namely the projectivization of the vector space structure of the elementary abelian group

),

),

and further, G does not act on this geometry, nor does it reflect any of the non-abelian structure (in both cases because the quotient is abelian).

However, it is an elementary result, which can be seen concretely as follows: the set of normal subgroups of a given index p form a projective space, namely the projective space

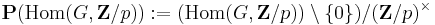

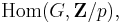

In detail, the space of homomorphisms from G to the (cyclic) group of order p,  is a vector space over the finite field

is a vector space over the finite field  A non-trivial such map has as kernel a normal subgroup of index p, and multiplying the map by an element of

A non-trivial such map has as kernel a normal subgroup of index p, and multiplying the map by an element of  (a non-zero number mod p) does not change the kernel; thus one obtains a map from

(a non-zero number mod p) does not change the kernel; thus one obtains a map from

to normal index p subgroups. Conversely, a normal subgroup of index p determines a non-trivial map to  up to a choice of "which coset maps to

up to a choice of "which coset maps to  which shows that this map is a bijection.

which shows that this map is a bijection.

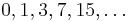

As a consequence, the number of normal subgroups of index p is

for some k;  corresponds to no normal subgroups of index p. Further, given two distinct normal subgroups of index p, one obtains a projective line consisting of

corresponds to no normal subgroups of index p. Further, given two distinct normal subgroups of index p, one obtains a projective line consisting of  such subgroups.

such subgroups.

For  the symmetric difference of two distinct index 2 subgroups (which are necessarily normal) gives the third point on the projective line containing these subgroups, and a group must contain

the symmetric difference of two distinct index 2 subgroups (which are necessarily normal) gives the third point on the projective line containing these subgroups, and a group must contain  index 2 subgroups – it cannot contain exactly 2 or 4 index 2 subgroups, for instance.

index 2 subgroups – it cannot contain exactly 2 or 4 index 2 subgroups, for instance.

See also

References

- Lam, T. Y. (March 2004), "On Subgroups of Prime Index", The American Mathematical Monthly 111 (3): 256–258, JSTOR 4145135, alternative download